KEY:

1662 = Revised along the lines of the Church of England’s 1662 BCP

1928 = Revised along the lines of the American 1928 BCP

1979 = As it appears in the current BCP of the Episcopal Church

1979*= Slight revision of current BCP of the Episcopal Church

ASB = As it appears in the Anglican Service Book (Church of the Good Shepherd, Rosemont, PA)

The Daily Office

Morning Prayer (1928)

Evening Prayer (1662)

Noonday Prayer (ASB)

Compline (ASB)

A Contemporary Daily Office (1979*, combined MP and EP)

Table of Suggested Canticles

The Great Litany (1928)

The Collects: Traditional (1979)

Seasons of the Year

Holy Days

Common of Saints

Various Occasions

The Collects: Contemporary (1979)

Seasons of the Year

Holy Days

Common of Saints

Various Occasions

Proper Liturgies for Special Days: Traditional (ASB)

A Penitential Order (1928, w/ imposition of ashes)

Palm Sunday

Maundy Thursday

Good Friday

Holy Saturday

The Great Vigil of Easter

Proper Liturgies for Special Days: Contemporary (1979)

Ash Wednesday

Palm Sunday

Maundy Thursday

Good Friday

Holy Saturday

The Great Vigil of Easter

Holy Baptism

Rite One (1928)

Rite Two (1979*)

The Holy Eucharist: Rite One

An Exhortation (1979, ASB)

The Decalogue: Traditional (ASB)

A Penitential Order: Traditional (ASB)

The Holy Eucharist (1928)

Alternate Eucharistic Prayer (1662)

The Proper Prefaces (ASB)

Prayers of the People: Traditional (ASB)

Offertory Sentences (ASB)

Communion of the Sick (ASB)

The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two

An Exhortation with Decalogue (1979)

A Penitential Order: Rite Two (1979)

The Holy Eucharist (1979, Eucharistic Prayer A)

Alternate Eucharistic Prayers (1979, Eucharistic Prayers B & D)

The Proper Prefaces (1979)

Prayers of the People: Contemporary (1979)

Offertory Sentences (1979)

Communion under Special Circumstances (1979)

Pastoral Offices

Holy Matrimony: Traditional (1928)

Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage (1979)

Thanksgiving for the Birth or Adoption of a Child: Rite One (ASB)

Thanksgiving for the Birth of Adoption of a Child: Rite Two (1979)

Reconciliation of a Penitent: Rite One (ASB)

Reconciliation of a Penitent: Rite Two (1979)

Ministration to the Sick: Rite One (ASB)

Ministration to the Sick: Rite Two (1979)

Ministration at the Time of Death: Rite One (ASB)

Ministration at the Time of Death: Rite Two (1979)

Burial of the Dead: Rite One (1928)

Burial of the Dead: Rite Two (1979)

Episcopal Services

Confirmation (1928)

Ordination of a Bishop (1928)

Ordination of a Priest (1928)

Ordination of a Deacon (1928)

Litany of Ordinations (1928)

Celebration of a New Ministry: Rite One (ASB)

Celebration of a New Ministry: Rite Two (1979)

The Psalter, or Psalms of David (Revised Standard Version)

Prayers and Thanksgivings (ASB, 1979)

A Catechism (1928)

Historical Documents of the Church (1979*)

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Friday, January 26, 2007

A One Book Solution? Part Two

In Part One, I stated that the Green Book was yet another attempt at (what I consider to be) a flawed strategy, and thus will fail to satisfy most Anglicans. People will continue to use whatever they’re accustomed to using: traditional folks will continue to use one version or another of the classic BCP, and contemporary folks will continue to use (in most cases) services from the 1979 BCP. Whether the AMiA leadership envisions the Green Book project to be a bona fide first step in producing a credible "Book of Alternative Services," or whether, following Toon, the Green Book is viewed more as an "interim measure" (the "bait and switch" strategy – see my earlier post), is difficult to say. However, in the final analysis, this particular “two-book” solution will simply be unable to live up to its design.

Now here's my radical idea: rather than starting with the template of the 1662 or 1928 BCP as the basis for new contemporary Cranmerian rites, why not instead start with the template of the 1979 BCP as the basis for restoring the traditional Cranmerian rites for a truly one-book result? Now hear me out, this is not as crazy as my readers may think. This plan would involve the following rather simple steps:

(1) Perform "restorative surgery" on the 1979 Rite One services (Daily Offices and Holy Eucharist) so that they reflect more accurately the text and spirit of the 1928 rites. (I would also remove the current alternative Eucharistic Prayer in Rite One, and replace it with a 1662-style alternative.)

(2) Include "Rite One" services that are not currently provided in the 1979 BCP, e.g., Baptism, Confirmation, Compline, Noonday Prayer, and the Pastoral Offices. (The Anglican Service Book – produced by the Church of the Good Shepherd in Rosemont, PA – is a great resource here since nearly everything of value in the 1979 BCP has been rendered in traditional language.)

(3) In the interest of keeping the size of the new BCP manageable, a revision committee working on such a project perhaps could consider excising some superfluous services and/or placing some services (e.g. Consecration of a Church) into a “Book of Occasional Services.”

(4) Redress the traditional/contemporary language balance (currently heavily weighted toward the contemporary). So, for instance, some offices (e.g. the Daily Offices and the Great Litany) are perhaps best left in their traditional (1928) forms and some contemporary (Rite Two) offices either conflated (e.g. Daily Offices) or discarded altogether. I'd also replace the Psalter with the RSV.

(5) Keep only two or at most three of the alternative Eucharistic Prayers in Rite Two. (My preference would be simply to remove Eucharistic Prayer C. Whatever is done, do not discard Eucharistic Prayer D!)

(6) Make other changes as deemed necessary to bring the new BCP in line with Anglican consensus, while continuing to maintain its comprehensiveness. (For example, include an introductory paragraph to the "Historical Documents" section that clearly states that the Church is NOT relegating these important statements to the dustbin of history.)

A radical plan? Yes, probably too radical for those who hate the 1979 Book. But it is a VERY doable plan and I think the best chance for a “one-book” solution currently being proposed.

In my next installment, I will provide a sample Table of Contents that will shed further light on what such a BCP would look like.

Now here's my radical idea: rather than starting with the template of the 1662 or 1928 BCP as the basis for new contemporary Cranmerian rites, why not instead start with the template of the 1979 BCP as the basis for restoring the traditional Cranmerian rites for a truly one-book result? Now hear me out, this is not as crazy as my readers may think. This plan would involve the following rather simple steps:

(1) Perform "restorative surgery" on the 1979 Rite One services (Daily Offices and Holy Eucharist) so that they reflect more accurately the text and spirit of the 1928 rites. (I would also remove the current alternative Eucharistic Prayer in Rite One, and replace it with a 1662-style alternative.)

(2) Include "Rite One" services that are not currently provided in the 1979 BCP, e.g., Baptism, Confirmation, Compline, Noonday Prayer, and the Pastoral Offices. (The Anglican Service Book – produced by the Church of the Good Shepherd in Rosemont, PA – is a great resource here since nearly everything of value in the 1979 BCP has been rendered in traditional language.)

(3) In the interest of keeping the size of the new BCP manageable, a revision committee working on such a project perhaps could consider excising some superfluous services and/or placing some services (e.g. Consecration of a Church) into a “Book of Occasional Services.”

(4) Redress the traditional/contemporary language balance (currently heavily weighted toward the contemporary). So, for instance, some offices (e.g. the Daily Offices and the Great Litany) are perhaps best left in their traditional (1928) forms and some contemporary (Rite Two) offices either conflated (e.g. Daily Offices) or discarded altogether. I'd also replace the Psalter with the RSV.

(5) Keep only two or at most three of the alternative Eucharistic Prayers in Rite Two. (My preference would be simply to remove Eucharistic Prayer C. Whatever is done, do not discard Eucharistic Prayer D!)

(6) Make other changes as deemed necessary to bring the new BCP in line with Anglican consensus, while continuing to maintain its comprehensiveness. (For example, include an introductory paragraph to the "Historical Documents" section that clearly states that the Church is NOT relegating these important statements to the dustbin of history.)

A radical plan? Yes, probably too radical for those who hate the 1979 Book. But it is a VERY doable plan and I think the best chance for a “one-book” solution currently being proposed.

In my next installment, I will provide a sample Table of Contents that will shed further light on what such a BCP would look like.

Labels:

Anglican,

BCP,

Contemporary,

Dissenting Anglican,

Liturgy,

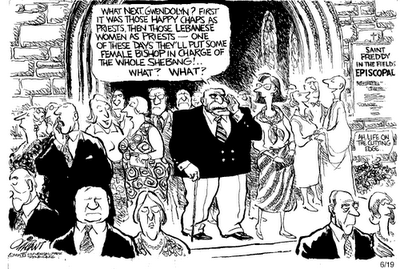

The Episcopal Church

Thursday, January 25, 2007

Is there a "one-book" solution for American Anglicans?

Once upon a time, unity around a common liturgy was a "given" for Anglicans... and then came the 1979 BCP of the Episcopal Church (USA), which, for many Anglicans, marked the end of "common worship" as a distinctive characteristic of the Anglican tradition, and the beginning of the end for Anglican unity overall. The end.

At least that's how many traditionalists tell the story. Those who support the new BCP contend that the inclusion of traditional "Rite One" services is enough deference paid to the old BCP to lay claim to continuity with it, and to satisfy traditionalists at the same time. Obviously, the detractors do not see things this way, and have ever since waged open warfare against it, and against modern rites in general, which makes the recent introduction of the AMiA's new Trial Liturgy (henceforth called "the Green Book") all the more intriguing.

However, do not think for a moment (despite my recent remarks) that the Green Book -- essentially the 1662 BCP in modern idiom -- necessarily represents a significant concession of defeat, or an acknowledgement of the need to modernize the idiom of worship, on the part of Dr. Peter Toon (the guiding hand behind the Green Book) and his followers. It is not even an admission that traditional and contemporary rites could (or even should) exist together within the same cover of some future BCP. Indeed, Dr. Toon has gone on record many times that, at most, the move to contemporize Cranmer should be viewed as an interim measure -- what I like to call the "bait and switch" solution. The ultimate goal is merely to wean contemporary Anglicans away from the 1979 BCP (and other "defective" modern rites). The beauty and the theological soundness of the Cranmerian liturgy, even as found in the Green Book (the "bait"), will do its magic by eventually winning the hearts of modern Anglicans and others back to Cranmer's liturgy and to its traditional Elizabethan era idiom as well (the "switch"). But will this tactic work? I think not, and here's why:

(1) The Green Book is not the first attempt to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy. In fact, many such projects have been attempted, and each one has produced less than stellar results -- ranging from the banal to the sophomoric. Simply put, the strategy to woo folks back to the classic BCP by introducing a contemporary version of it does not seem to work, at least not very well. This begs at least two questions: first, why hasn't it worked? And, second, why add one more alternative liturgy to the plethora of alternatives already out there?

(2) In part, the first question can be answered by noting that the strategy is built on two faulty premises: first, that taking the "thees, thous, and vouchsafes" out of the Cranmerian rites will remove a stumbling block to those Anglicans who, due to years of disuse and/or non-exposure to proper Prayerbook language, are put off by such archaic words. Second, the assertion is made that modern Anglicans only use the 1979 BCP because no better alternative is available to them. Provide a Cranmerian alternative in modern English (e.g. the Green Book), or so it is argued, and modern Anglicans will drop the '79 Book like a hot potato. Both premises are faulty if only for the fact that the "thees, thous, and vouchsafes" are not the only archaicisms, and probably not even the most imposing ones, in the traditional BCP. Issues of lengthiness, cadence, complex sentence structure, complicated parallelisms, rubrical rigidness, inflexibility, overdone didacticism, dearth of celebration, and obscure terminology certainly play their roles in the general lack of appeal to the modern liturgical palate. Yet these issues are typically ignored in attempts to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy.

(3) But there is another, more important reason: many Anglicans, even conservative ones, actually like the 1979 BCP, despite some of its flaws, even if they are somewhat hesitant to admit this to the more vocal opposition. For years we've been hearing about how baaaaad the 1979 BCP was, that folks have been somewhat hesitant and intimidated to defend it in the face of fierce verbal assault. But in actuality, as the practice of many Anglicans bears out, the '79 Book turns out to be a very versatile liturgy with many laudable features. The scholarship behind it is really quite outstanding, even if it is also quite broad. There is much in it that is appealing to modern Anglicans: its "shape," the restoration of ancient forms and rites, its "patristic eclectisim," and its pastoral tone. I'm not suggesting for a moment that the Book doesn't have flaws and deficiencies; only that the '79 Book does not come close to being the demon-possessed tome that its detractors make it out to be.

Finally, let me end by humbly suggesting that the future course of American Anglicanism should strive to achieve two worthy goals. First, I firmly believe that it is a good, right, and appropriate thing for Anglicans to seek to preserve Cranmer's liturgy, and to promote the frequent use of it, in its original idiom no less. (Despite what my readers may unduly conclude from this article, I defy anyone to demonstrate a love for Cranmer's liturgy that surpasses my own. After all, I would never dream of dishonoring Cranmer's liturgy by "translating" it into contemporary idiom.) The second worthy goal is to preserve what has proven to be laudable and edifying in the contemporary Anglican liturgical experiment, many of the features found in the 1979 BCP. Can this be done? And can it be done within one cover? Is there a "one-book" solution? I don't know. But I will lay out for my readers some idea of how a "one-book solution" might look in my next two installments.

Until next time.

At least that's how many traditionalists tell the story. Those who support the new BCP contend that the inclusion of traditional "Rite One" services is enough deference paid to the old BCP to lay claim to continuity with it, and to satisfy traditionalists at the same time. Obviously, the detractors do not see things this way, and have ever since waged open warfare against it, and against modern rites in general, which makes the recent introduction of the AMiA's new Trial Liturgy (henceforth called "the Green Book") all the more intriguing.

However, do not think for a moment (despite my recent remarks) that the Green Book -- essentially the 1662 BCP in modern idiom -- necessarily represents a significant concession of defeat, or an acknowledgement of the need to modernize the idiom of worship, on the part of Dr. Peter Toon (the guiding hand behind the Green Book) and his followers. It is not even an admission that traditional and contemporary rites could (or even should) exist together within the same cover of some future BCP. Indeed, Dr. Toon has gone on record many times that, at most, the move to contemporize Cranmer should be viewed as an interim measure -- what I like to call the "bait and switch" solution. The ultimate goal is merely to wean contemporary Anglicans away from the 1979 BCP (and other "defective" modern rites). The beauty and the theological soundness of the Cranmerian liturgy, even as found in the Green Book (the "bait"), will do its magic by eventually winning the hearts of modern Anglicans and others back to Cranmer's liturgy and to its traditional Elizabethan era idiom as well (the "switch"). But will this tactic work? I think not, and here's why:

(1) The Green Book is not the first attempt to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy. In fact, many such projects have been attempted, and each one has produced less than stellar results -- ranging from the banal to the sophomoric. Simply put, the strategy to woo folks back to the classic BCP by introducing a contemporary version of it does not seem to work, at least not very well. This begs at least two questions: first, why hasn't it worked? And, second, why add one more alternative liturgy to the plethora of alternatives already out there?

(2) In part, the first question can be answered by noting that the strategy is built on two faulty premises: first, that taking the "thees, thous, and vouchsafes" out of the Cranmerian rites will remove a stumbling block to those Anglicans who, due to years of disuse and/or non-exposure to proper Prayerbook language, are put off by such archaic words. Second, the assertion is made that modern Anglicans only use the 1979 BCP because no better alternative is available to them. Provide a Cranmerian alternative in modern English (e.g. the Green Book), or so it is argued, and modern Anglicans will drop the '79 Book like a hot potato. Both premises are faulty if only for the fact that the "thees, thous, and vouchsafes" are not the only archaicisms, and probably not even the most imposing ones, in the traditional BCP. Issues of lengthiness, cadence, complex sentence structure, complicated parallelisms, rubrical rigidness, inflexibility, overdone didacticism, dearth of celebration, and obscure terminology certainly play their roles in the general lack of appeal to the modern liturgical palate. Yet these issues are typically ignored in attempts to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy.

(3) But there is another, more important reason: many Anglicans, even conservative ones, actually like the 1979 BCP, despite some of its flaws, even if they are somewhat hesitant to admit this to the more vocal opposition. For years we've been hearing about how baaaaad the 1979 BCP was, that folks have been somewhat hesitant and intimidated to defend it in the face of fierce verbal assault. But in actuality, as the practice of many Anglicans bears out, the '79 Book turns out to be a very versatile liturgy with many laudable features. The scholarship behind it is really quite outstanding, even if it is also quite broad. There is much in it that is appealing to modern Anglicans: its "shape," the restoration of ancient forms and rites, its "patristic eclectisim," and its pastoral tone. I'm not suggesting for a moment that the Book doesn't have flaws and deficiencies; only that the '79 Book does not come close to being the demon-possessed tome that its detractors make it out to be.

Finally, let me end by humbly suggesting that the future course of American Anglicanism should strive to achieve two worthy goals. First, I firmly believe that it is a good, right, and appropriate thing for Anglicans to seek to preserve Cranmer's liturgy, and to promote the frequent use of it, in its original idiom no less. (Despite what my readers may unduly conclude from this article, I defy anyone to demonstrate a love for Cranmer's liturgy that surpasses my own. After all, I would never dream of dishonoring Cranmer's liturgy by "translating" it into contemporary idiom.) The second worthy goal is to preserve what has proven to be laudable and edifying in the contemporary Anglican liturgical experiment, many of the features found in the 1979 BCP. Can this be done? And can it be done within one cover? Is there a "one-book" solution? I don't know. But I will lay out for my readers some idea of how a "one-book solution" might look in my next two installments.

Until next time.

Labels:

Anglican,

BCP,

Contemporary,

Dissenting Anglican,

Liturgy,

The Episcopal Church

Monday, January 22, 2007

Karl Barth's comment on the plurality of churches

I pulled this quote of Karl Barth from Hans Urs von Balthasar's article on A Divided Church (see below). Barth's comments stand on their own as a classic appraisal of our current divisions, and so are worthy of our consideration.

++++++++++++++++

The plurality of churches ... should not be interpreted as something willed by God, as a normal unfolding of the wealth of grace given to mankind in Jesus Christ [nor as] a necessary trait of the visible, empirical Church, in contrast to the invisible, ideal, essential Church. Such a distinction is entirely foreign to the New Testament because, in this regard also, the Church of Jesus Christ is one. She is invisible in terms of the grace of the Word of God and of the Holy Spirit, . . . but visible in signs in the multitude of those who profess their adherence to her; she is visible as a community and in her community ministry, visible in her service of the word and sacrament.... It is impossible to escape from the visible Church to the invisible.

If ecumenical endeavor is pursued along the lines of such a distinction, however fine the words may sound, it is philosophy of history and philosophy of society. it is not theology. People who do this are producing their own ideas in order to get rid of the question of the Church's unity, instead of facing the question posed by Christ.... If we listen to Christ, . we do not exist above the differences that divide the Church: we exist in them.... In fact, we should not attempt to explain the plurality of churches at all. We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.... We should understand the plurality as a mark of our guilt (K. Barth, Die Kirche und die Kirchen. Theol., 9- 10).

Saturday, January 20, 2007

A Divided Church? by Hans Urs von Balthasar

There's much in here that I like (particularly the quote from Barth), but it's interesting to see how this eminent theologian struggles with this issue.

A Divided Church?

by Hans Urs von Balthasar

from the Third Volume of the Theo-Dramatic

The division of the Church, brought about by sin, is rendered all the easier because of the distribution within her of various charisms and offices. At the very outset the community must be warned against envy and jealousy: someone else has been given something I do not possess; but, in the dispensation of love, it is for the greatest advantage of the whole in which I share. The eye sees on behalf of the whole body, and so on (1 Cor 12).

The administration of charisms presupposes selfless love on the part of all (1Cor 13). It takes only the slightest change of perspective to highlight the special nature of a charism--perhaps its striking and attractive side-making it seem more important than the Church's organic unity. Thus parties arise, often through no fault of the bearers of charisms. So Paul exhorts his hearers: "I appeal to you, brethren.... that there be no dissensions [schismata] among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment. For it has been reported to me ... that there is quarrelling among you, my brethren. What I mean is that each one of you says, 'I belong to Paul', or 'I belong to Apollos', or 'I belong to Cephas. . . .' Is Christ divided? Was Paul crucified for you?" (1 Cor 1: 10-13).

Of course, there is a difference between schisms within the Church and the ultimate schism that separates people from the unity of the institutional Church. But there can be no doubt that the former were the cause of the latter. Sin in the Church is the origin of the (equally sinful) separation from the Church. The process can last for hundreds of years within the Church--think of the long prelude to the schism with the East and to the Reformation--but it can always be traced back.

Not that this justifies the ultimate rupture. A slackening of the love that preserves and builds up the Church's catholicity is the beginning, however hidden, of all division in the Church: ‘ubi peccata, ibi multitudo.’ ‘Where there are sins. there is multiplicity, divisions, erroneous teachings and discord. But where there is virtue, there is oneness, union; thus all believers were 'of one heart and one soul'. (Origen, In Ez. hom. 9)

This raises the grave question whether, and when, the Church, divided internally and often externally as well, ceases to be a single person in the theo-drama. Two principles are crucial here. The first is that the Church, both as a community of saints and as an institution, is designed and equipped to sustain and save the sinners who dwell within her; she is *corpus permixtum* and must not separate herself from them as a Church of the "pure", elect", "predestined", and so forth.

To that extent, she has to continue to endure the inner tension between her ideal and her fallen reality, endeavoring to draw what is at her periphery toward the center. Thus the unity that encompasses her (the "net") is a principle of this kind: it can hold on to those who are estranged from her provided they have not deliberately renounced her.

At this borderline, however, the other principle takes over: theologically speaking, there absolutely cannot be a plurality of Churches of Christ; if such a plurality empirically exists, these several Christian churches cannot represent theological "persons". It follows that it is impossible, by a process of abstraction, to deduce some common denominator from the historical plurality and so posit an overall concept of the one Church; for the latter's unity is not that of a species: it is a concrete and individual, unique unity, corresponding to the unique Christ who founded her.

We would do well to listen to Karl Barth at this point:

‘The plurality of churches ... should not be interpreted as something willed by God, as a normal unfolding of the wealth of grace given to mankind in Jesus Christ [nor as] a necessary trait of the visible, empirical Church, in contrast to the invisible, ideal, essential Church. Such a distinction is entirely foreign to the New Testament because, in this regard also, the Church of Jesus Christ is one. She is invisible in terms of the grace of the Word of God and of the Holy Spirit, . . . but visible in signs in the multitude of those who profess their adherence to her; she is visible as a community and in her community ministry, visible in her service of the word and sacrament.... It is impossible to escape from the visible Church to the invisible.

'If ecumenical endeavor is pursued along the lines of such a distinction, however fine the words may sound, it is philosophy of history and philosophy of society. it is not theology. People who do this are producing their own ideas in order to get rid of the question of the Church's unity, instead of facing the question posed by Christ.... If we listen to Christ, . we do not exist above the differences that divide the Church: we exist in them.... In fact, we should not attempt to explain the plurality of churches at all. We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.... We should understand the plurality as a mark of our guilt’ (K. Barth, Die Kirche und die Kirchen. Theol., 9- 10).

We search the New Testament in vain, therefore, if we are looking for guidelines as to how separated churches should get on together; all we shall find there are instructions for avoiding such divisions.

While it is possible to say, with the Second Vatican Council, that "some, even very many, of the most significant elements and endowments that together go to build up and give life to the Church herself can exist" in those Christian communities that have deliberately distanced themselves from the institution of the Catholica; and while we may recognize that "men who believe in Christ and have been properly baptized are put in some, though imperfect, communion with the Catholic Church", this does not mean that such communities constitute separate theological persons over against the Catholica.

With regard to the relationship between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches, the question is whether mutual estrangement has proceeded so far that we are obliged to speak of two "Churches", or whether, in point of historical fact, unity "has never ceased to exist at a deep level" (L. Bouyer, The Church of God: "Theology of the Church").

There have also been attempts to suggest that there is a theological ‘necessity’ behind the phenomenon of schisms, ‘whether on the basis of the Old Testament schism between the North and South Kingdoms’ or arising out of the ‘primal split’ between Judaism and the Gentile world at the founding of the Church. With regard to the former split, however, the tribes of Israel had never been a unity comparable to that of the Body of Christ but a ‘confederation of diverse tribal groups’ that had only lately been united ‘in the person’ of the monarch. With regard to the latter split, it would be difficult to maintain that the Israel that refused Christ was responsible for disputes within the Christian Church; according to Paul, the unity of Christians is based on an entirely different principle (Eph 4:3 ff.) from that of the Jewish ‘sects’ (and Paul had been a member of one of them).

Precisely this principle of unity, however--the Eucharist of the pneumatic Lord--is a wholly new and incomparable principle, and this makes the initial split, which becomes aggravated into full-blown schism, to be practically irreversible. Urged by the most elementary sense of Christian duty, the ‘ecumenical movement’ must indeed tirelessly exert itself for the reunion of the separated ‘churches’. By doing this many partial successes can doubtless be achieved: for instance, the reduction of mutual misunderstandings, suspicions and denigrations.

But the fact remains that the group of churches separated from the Catholic Church has, by this very separation, necessarily gotten rid of the visible symbol of unity, the papacy, and this results in a situation in which our partners in dialogue (including the Orthodox) do not possess any authority which is recognized by all the believers and as such can officially represent these. In each case we are dealing with individual groups or bishops who regularly divide themselves into a party of agreement and a party of objection whenever reunion with the Catholic Church is contemplated. And, seemingly, the best that such groups can produce is an offer of abstract catholicity arrived at by overlooking real differences. We have already described such ‘catholicity’ as being plainly unacceptable.

However fruitful and instructive the ecumenical dialogue between Churches is, exemplary holiness will show not only that obedience to the Church (as understood by Catholics) can be integrated into Christian *agape* but that it is actually an indispensable part of the latter and of the discipleship of Christ.

Finally, while the Church's missionary task is to give witness to the world, the chimera of the divided Church shows just how shaky her self-transcendence into the world is. Indeed, it becomes increasingly precarious, the more Christian sects proliferate. Even if the worst stumbling blocks were overcome by making pacts between missions professing different beliefs, the fundamental stumbling block would remain as far as the recipient of missionary activity is concerned.

Nor can it be removed by portraying the diversity of Christian expressions as something harmless, something arising necessarily as a result of historical development, or even as something that brings blessing. To do this would simply be to obscure Jesus' original wish even more. To repeat the words of Karl Barth on the phenomenon of division in the Church: ‘We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.’"

by Hans Urs von Balthasar

from the Third Volume of the Theo-Dramatic

The division of the Church, brought about by sin, is rendered all the easier because of the distribution within her of various charisms and offices. At the very outset the community must be warned against envy and jealousy: someone else has been given something I do not possess; but, in the dispensation of love, it is for the greatest advantage of the whole in which I share. The eye sees on behalf of the whole body, and so on (1 Cor 12).

The administration of charisms presupposes selfless love on the part of all (1Cor 13). It takes only the slightest change of perspective to highlight the special nature of a charism--perhaps its striking and attractive side-making it seem more important than the Church's organic unity. Thus parties arise, often through no fault of the bearers of charisms. So Paul exhorts his hearers: "I appeal to you, brethren.... that there be no dissensions [schismata] among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment. For it has been reported to me ... that there is quarrelling among you, my brethren. What I mean is that each one of you says, 'I belong to Paul', or 'I belong to Apollos', or 'I belong to Cephas. . . .' Is Christ divided? Was Paul crucified for you?" (1 Cor 1: 10-13).

Of course, there is a difference between schisms within the Church and the ultimate schism that separates people from the unity of the institutional Church. But there can be no doubt that the former were the cause of the latter. Sin in the Church is the origin of the (equally sinful) separation from the Church. The process can last for hundreds of years within the Church--think of the long prelude to the schism with the East and to the Reformation--but it can always be traced back.

Not that this justifies the ultimate rupture. A slackening of the love that preserves and builds up the Church's catholicity is the beginning, however hidden, of all division in the Church: ‘ubi peccata, ibi multitudo.’ ‘Where there are sins. there is multiplicity, divisions, erroneous teachings and discord. But where there is virtue, there is oneness, union; thus all believers were 'of one heart and one soul'. (Origen, In Ez. hom. 9)

This raises the grave question whether, and when, the Church, divided internally and often externally as well, ceases to be a single person in the theo-drama. Two principles are crucial here. The first is that the Church, both as a community of saints and as an institution, is designed and equipped to sustain and save the sinners who dwell within her; she is *corpus permixtum* and must not separate herself from them as a Church of the "pure", elect", "predestined", and so forth.

To that extent, she has to continue to endure the inner tension between her ideal and her fallen reality, endeavoring to draw what is at her periphery toward the center. Thus the unity that encompasses her (the "net") is a principle of this kind: it can hold on to those who are estranged from her provided they have not deliberately renounced her.

At this borderline, however, the other principle takes over: theologically speaking, there absolutely cannot be a plurality of Churches of Christ; if such a plurality empirically exists, these several Christian churches cannot represent theological "persons". It follows that it is impossible, by a process of abstraction, to deduce some common denominator from the historical plurality and so posit an overall concept of the one Church; for the latter's unity is not that of a species: it is a concrete and individual, unique unity, corresponding to the unique Christ who founded her.

We would do well to listen to Karl Barth at this point:

‘The plurality of churches ... should not be interpreted as something willed by God, as a normal unfolding of the wealth of grace given to mankind in Jesus Christ [nor as] a necessary trait of the visible, empirical Church, in contrast to the invisible, ideal, essential Church. Such a distinction is entirely foreign to the New Testament because, in this regard also, the Church of Jesus Christ is one. She is invisible in terms of the grace of the Word of God and of the Holy Spirit, . . . but visible in signs in the multitude of those who profess their adherence to her; she is visible as a community and in her community ministry, visible in her service of the word and sacrament.... It is impossible to escape from the visible Church to the invisible.

'If ecumenical endeavor is pursued along the lines of such a distinction, however fine the words may sound, it is philosophy of history and philosophy of society. it is not theology. People who do this are producing their own ideas in order to get rid of the question of the Church's unity, instead of facing the question posed by Christ.... If we listen to Christ, . we do not exist above the differences that divide the Church: we exist in them.... In fact, we should not attempt to explain the plurality of churches at all. We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.... We should understand the plurality as a mark of our guilt’ (K. Barth, Die Kirche und die Kirchen. Theol., 9- 10).

We search the New Testament in vain, therefore, if we are looking for guidelines as to how separated churches should get on together; all we shall find there are instructions for avoiding such divisions.

While it is possible to say, with the Second Vatican Council, that "some, even very many, of the most significant elements and endowments that together go to build up and give life to the Church herself can exist" in those Christian communities that have deliberately distanced themselves from the institution of the Catholica; and while we may recognize that "men who believe in Christ and have been properly baptized are put in some, though imperfect, communion with the Catholic Church", this does not mean that such communities constitute separate theological persons over against the Catholica.

With regard to the relationship between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches, the question is whether mutual estrangement has proceeded so far that we are obliged to speak of two "Churches", or whether, in point of historical fact, unity "has never ceased to exist at a deep level" (L. Bouyer, The Church of God: "Theology of the Church").

There have also been attempts to suggest that there is a theological ‘necessity’ behind the phenomenon of schisms, ‘whether on the basis of the Old Testament schism between the North and South Kingdoms’ or arising out of the ‘primal split’ between Judaism and the Gentile world at the founding of the Church. With regard to the former split, however, the tribes of Israel had never been a unity comparable to that of the Body of Christ but a ‘confederation of diverse tribal groups’ that had only lately been united ‘in the person’ of the monarch. With regard to the latter split, it would be difficult to maintain that the Israel that refused Christ was responsible for disputes within the Christian Church; according to Paul, the unity of Christians is based on an entirely different principle (Eph 4:3 ff.) from that of the Jewish ‘sects’ (and Paul had been a member of one of them).

Precisely this principle of unity, however--the Eucharist of the pneumatic Lord--is a wholly new and incomparable principle, and this makes the initial split, which becomes aggravated into full-blown schism, to be practically irreversible. Urged by the most elementary sense of Christian duty, the ‘ecumenical movement’ must indeed tirelessly exert itself for the reunion of the separated ‘churches’. By doing this many partial successes can doubtless be achieved: for instance, the reduction of mutual misunderstandings, suspicions and denigrations.

But the fact remains that the group of churches separated from the Catholic Church has, by this very separation, necessarily gotten rid of the visible symbol of unity, the papacy, and this results in a situation in which our partners in dialogue (including the Orthodox) do not possess any authority which is recognized by all the believers and as such can officially represent these. In each case we are dealing with individual groups or bishops who regularly divide themselves into a party of agreement and a party of objection whenever reunion with the Catholic Church is contemplated. And, seemingly, the best that such groups can produce is an offer of abstract catholicity arrived at by overlooking real differences. We have already described such ‘catholicity’ as being plainly unacceptable.

However fruitful and instructive the ecumenical dialogue between Churches is, exemplary holiness will show not only that obedience to the Church (as understood by Catholics) can be integrated into Christian *agape* but that it is actually an indispensable part of the latter and of the discipleship of Christ.

Finally, while the Church's missionary task is to give witness to the world, the chimera of the divided Church shows just how shaky her self-transcendence into the world is. Indeed, it becomes increasingly precarious, the more Christian sects proliferate. Even if the worst stumbling blocks were overcome by making pacts between missions professing different beliefs, the fundamental stumbling block would remain as far as the recipient of missionary activity is concerned.

Nor can it be removed by portraying the diversity of Christian expressions as something harmless, something arising necessarily as a result of historical development, or even as something that brings blessing. To do this would simply be to obscure Jesus' original wish even more. To repeat the words of Karl Barth on the phenomenon of division in the Church: ‘We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.’"

Labels:

Balthasar,

Barth,

Contemporary,

Ecclesiology,

Roman Catholic

AMiA Trial Liturgy

Matt Kennedy over at Standfirm has just gleefully announced the publication of the AMiA's new trial Book of Common Prayer in contemporary language, a work in which Peter Toon had an overseeing hand. The Eucharistic liturgy can be seen HERE. A few months ago, a friend of mine in the AMiA sent me a copy of the trial liturgy (the "Green Book"). So I've had some time to look at it, though admittedly it has been a bit of a chore to get through.

My intial reaction to this was amazement that Dr. Toon would have anything to do with a project to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy. Could it be that Toon has succumbed to the theory that the only way to preserve a literary classic is to alter its idiom? (which sort of defeats the purpose, no?)

I can only account for this by supposing that (1) Toon has ever so quietly conceded defeat in the contemporary language debate, and (2) he has let his hatred of the 1979 BCP blind himself to the fact that he will now be rememberd as the progenitor of a banal and hackneyed "translation" (the most apt term here) of Cranmer's once majestic liturgy. Oh well.

My intial reaction to this was amazement that Dr. Toon would have anything to do with a project to contemporize Cranmer's liturgy. Could it be that Toon has succumbed to the theory that the only way to preserve a literary classic is to alter its idiom? (which sort of defeats the purpose, no?)

I can only account for this by supposing that (1) Toon has ever so quietly conceded defeat in the contemporary language debate, and (2) he has let his hatred of the 1979 BCP blind himself to the fact that he will now be rememberd as the progenitor of a banal and hackneyed "translation" (the most apt term here) of Cranmer's once majestic liturgy. Oh well.

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

The question of Catholicism

“I would like to ask in all seriousness whether Protestantism can be a real answer to anyone for whom Catholicism has never been a real question – whether we still have any real business with the church of the Reformation if in the meantime we have left alone the counterpart with which it struggled. And I would like to issue a warning of the unhappy awakening which might some day follow such detachment. Those who know Catholicism even a little know how deceptive its remoteness and strangeness are, how uncannily close to us it really is, how urgent and vital the questions it puts to us are, and how inherently impossible is the possibility of not listening seriously to those questions once they have been heard.”

—Karl Barth,“Der römische Katholizismus als Frage an die Protestantische Kirche,” in Vorträge und kleinere Arbeiten 1925-1930, ed. Hermann Schmidt (Zurich: TVZ, 1994), p. 313.

Biretta tip to Ben Meyers over at Faith and Theology.

—Karl Barth,“Der römische Katholizismus als Frage an die Protestantische Kirche,” in Vorträge und kleinere Arbeiten 1925-1930, ed. Hermann Schmidt (Zurich: TVZ, 1994), p. 313.

Biretta tip to Ben Meyers over at Faith and Theology.

The Visible Church: My continuing conversation with "Anonymous"

ANON: "One" in what way? If you offer with the vague "in Christ", it is eerily similar to "invisible Church".

LEXORANDI2: The invisible Church model, originating with the Lutherans, makes personal faith or belief determinative of one’s membership in the Church. In such a model, the visible Church and her sacraments are secondary and non-determinative. All that counts is one’s personal faith. Thus you are right be concerned about this.

But that is not what I’m saying at all. Rather, baptism – a visible sign – is the determinative boundary of the Church. One is either baptized or not, and with the claim of baptism comes the responsibility to assent to the Church’s faith and teaching, which includes continuing “in the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread, and in the prayers.”

When I, as an Anglican, confess my “oneness” with the Roman Catholic or the Eastern Orthodox adherent I confess primarily a common baptism and a common faith (i.e., the Faith of the Church Catholic articulated in the Creed). But with this confession is also my affirmation that the respective ecclesial communities to which they belong are true, visible churches – part of the “one Church” that I confess in the Creed.

I suspect that your discomfort with the Anglican position (at least THIS Anglican’s position) is not only the explicit recognition of other apostolically-constituted churches (e.g., Roman Catholic, Orthodox), but also that other communities, whose apostolic pedigrees may be in question, are not explicitly “unrecognized.” I can only respond with something that a wise Eastern Orthodox priest once told me, “We can show you where the Church is, but we cannot always show you where it is not.” That Anglicans tend to err on the side of charity with respect to non-episcopal bodies is readily to be admitted. But I tend to see that as a virtue, not a vice.

LEXORANDI2: The invisible Church model, originating with the Lutherans, makes personal faith or belief determinative of one’s membership in the Church. In such a model, the visible Church and her sacraments are secondary and non-determinative. All that counts is one’s personal faith. Thus you are right be concerned about this.

But that is not what I’m saying at all. Rather, baptism – a visible sign – is the determinative boundary of the Church. One is either baptized or not, and with the claim of baptism comes the responsibility to assent to the Church’s faith and teaching, which includes continuing “in the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, in the breaking of bread, and in the prayers.”

When I, as an Anglican, confess my “oneness” with the Roman Catholic or the Eastern Orthodox adherent I confess primarily a common baptism and a common faith (i.e., the Faith of the Church Catholic articulated in the Creed). But with this confession is also my affirmation that the respective ecclesial communities to which they belong are true, visible churches – part of the “one Church” that I confess in the Creed.

I suspect that your discomfort with the Anglican position (at least THIS Anglican’s position) is not only the explicit recognition of other apostolically-constituted churches (e.g., Roman Catholic, Orthodox), but also that other communities, whose apostolic pedigrees may be in question, are not explicitly “unrecognized.” I can only respond with something that a wise Eastern Orthodox priest once told me, “We can show you where the Church is, but we cannot always show you where it is not.” That Anglicans tend to err on the side of charity with respect to non-episcopal bodies is readily to be admitted. But I tend to see that as a virtue, not a vice.

Monday, January 15, 2007

A Few More Links

I'm still doing some house cleaning of my blog, as well as adding more features and some links. Check out the following blogs:

Axegrinder (long overdue to be added)

Disruptive Grace

Elysium

Anglican Ethos-Theological Resources

A-C Ruminations

The Sarabite

Per Caritatem

Evangelical Catholicism

Axegrinder (long overdue to be added)

Disruptive Grace

Elysium

Anglican Ethos-Theological Resources

A-C Ruminations

The Sarabite

Per Caritatem

Evangelical Catholicism

Friday, January 12, 2007

Sacramental Causality

My friend Jeff over at meam-commemorationem recently published a "teaser" from an article critiquing Roman Catholic theologian L-M. Chauvet's postmodern take on Aquinas. Hopefully we can encourage Jeff to publish more entries on this article on his blog. Personally, I have profited greatly from Chauvet's Symbol and Sacrament, and I can already tell from the brief excerpt that the author is going to push a few of my buttons.

The entire article can be found HERE.

The entire article can be found HERE.

The Anglican Practice of Open Communion: A "Barthian" Take

.jpg)

A question from the comment section of an earlier entry ("My Third Reason for Remaining Anglican" - Saturday, January 6, 2007):

DMARTIN ASKS: Do Anglicans believe that to share the Body and Blood of Christ is an act of full communion or not?

LEXORANDI2: Obviously, I can only give you one Anglican's perspective on this, but, YES, this is certainly the principle behind the practice of open communion in Anglican churches, even if institutionally (canonically) our respective ecclesial communities (i.e. churches) do not yet live into this reality.

I find it helpful to appeal to Barth's objectivist theology in support of the "open Table" practice, particularly the question of what is real and unreal about the Christian and the Church in light of our union in Christ. What is real about the Church in Christ (objectively and eternally so) is the Church's unicity and holiness. Disunity and corruption -- the very things we unhappily "live into" -- are unreal, and thus are things destined to nothingness. By "living into" them (through schism and apostasy) we improperly reify the very things that have been abolished in Christ.

That being said, over the course of my ministry I have become increasingly passionate in my advocacy for the "open Table." For, despite our tenacity to live into the unreal (with respect to such things as "orders" and tertiary differences in doctrine), I am convinced that the Anglican tradition attains her highest degree of "living into the reality of what we already are in Christ" in the celebration of the sacraments via her "open Table."

Obviously, she fails miserably in other ways...

(I direct my readers to revisit an earlier blog entry --Dialogue with Barth-- for a further elaboration on the real and unreal distinction.)

DMARTIN ASKS: Do Anglicans believe that to share the Body and Blood of Christ is an act of full communion or not?

LEXORANDI2: Obviously, I can only give you one Anglican's perspective on this, but, YES, this is certainly the principle behind the practice of open communion in Anglican churches, even if institutionally (canonically) our respective ecclesial communities (i.e. churches) do not yet live into this reality.

I find it helpful to appeal to Barth's objectivist theology in support of the "open Table" practice, particularly the question of what is real and unreal about the Christian and the Church in light of our union in Christ. What is real about the Church in Christ (objectively and eternally so) is the Church's unicity and holiness. Disunity and corruption -- the very things we unhappily "live into" -- are unreal, and thus are things destined to nothingness. By "living into" them (through schism and apostasy) we improperly reify the very things that have been abolished in Christ.

That being said, over the course of my ministry I have become increasingly passionate in my advocacy for the "open Table." For, despite our tenacity to live into the unreal (with respect to such things as "orders" and tertiary differences in doctrine), I am convinced that the Anglican tradition attains her highest degree of "living into the reality of what we already are in Christ" in the celebration of the sacraments via her "open Table."

Obviously, she fails miserably in other ways...

(I direct my readers to revisit an earlier blog entry --Dialogue with Barth-- for a further elaboration on the real and unreal distinction.)

Tuesday, January 09, 2007

Monday, January 08, 2007

50 reasons why American Evangelicalism will be irrelevant by mid-century

Okay, I suppose some of these people are respectable. But on the whole this list is a frightening look at the state of American Christianity:

CLICK HERE

Biretta tip to T-1-9.

CLICK HERE

Biretta tip to T-1-9.

Saturday, January 06, 2007

My Third Reason for Remaining Anglican

What follows is my response to an anonymous correspondent who left an insightful comment on my previous post It's all Greek to me?? Hardly... (18 December 2006). Within this response I elaborate briefly on my third reason for remaining Anglican.

+++++++

ANONYMOUS: What separates Rome, the EO, and the Anglicans is ecclesiology more than any other thing. If one was to believe that the Church is defined by the Pope that person would have no choice but to be in communion with Rome. If one was to believe in the ecclesial ultimacy of the EO that person would of course join the EO. If one wants to be eclectic or inclusive, they go to the Anglicans. The red herrings of molester-priests in the RCC, xenophobia in the EO, or apostasy amongst the Anglican episcopate is really not relevant. Objectively speaking, either all three groups are wrong in their ecclesiology or one of them is right. Your personal comfort because of socialization or a desire for a particular liturgy shouldn't trump or determine how you define "Church" as you confess it in the Creed.

LEXORANDI2: I couldn’t have said this better myself. THE theological issue separating Romanism, Byzantinism, and Anglicanism is ecclesiology, which leads into my third reason why I remain an Anglican: Anglicanism views eclecticism and inclusiveness as a virtue, if not the very heart of true Catholicism.

In this respect, Anglicanism looks more like the pre-schism (pre-1054) Church than do the alternatives. When I look at the Roman Church or the Eastern churches (or the Oriental Orthodox bodies for that matter), I see eminent apostolic churches that hold essentially to the same faith that I do as an Anglican. Nothing in my Anglican ecclesiology prevents me from affirming them, or any of the baptized, as full brothers and sisters in Christ, nor forbids them a place at the Table. Paradoxically, it is my affirmation of the same that prevents the very fellowship with RC's and EO's that I as an Anglican so desire. So, in this respect, what I see in Anglicanism is what I believe that Rome or Byzantium SHOULD BE.

ANONYMOUS: If the writer had a firm allegiance to his ecclesiastial affiliation he wouldn't have even had the thought of switching; in fact the mere thought of joining something that defines out of the Church his entire tradition post-1054 would have been less than appealing. RC's and EO's don't daydream about being anything but what they are because they have a strong position on what they are confessing about "Church" in the Creed. Anglicans need to develop the same strength, but how can they when you can gather a group of conservative Anglicans and no two agree on the past or the future?

LEXORANDI2: Given the present troubles within our Communion (to which Rome’s troubles with “molester-priests” or Byzantine xenophobia hardly compare), it takes a rather hardhearted person not to understand the fears and, yes, even doubts, that weigh heavily on the minds of many otherwise committed Anglicans as they see their tradition unraveling around them in the face of overt apostasy, and perhaps even - God forbid - the beginning of the end of the Anglican experiment. I also find your generalization of the comparable allegiances of RC's and EO's amusing in that I know perhaps ten times more RC and EO converts to Protestantism (and Anglicanism) than I do the reverse. Hmmm... I wonder if any of these converts ever "daydreamed" about being something else before they jumped ship?

Like I suggested before, when I look at Rome and Byzantium I see communions that should, in the interest of a more consistent catholicism, be more "Anglican." This should be a matter of concern for someone like you, because I suspect that I am not the only Anglican "daydreamer" who feels this way. If Anglicanism falls irreparably apart, there will no doubt be many Anglicans finding new homes in one of the two remaining apostolic communions, which inevitably means that these communions will indeed become more "Anglican" over time. Perhaps this will mean the end of ecclesial ultimacy? (As they say, every cloud has a silver lining.)

Friday, January 05, 2007

Additions to my blog list

I just added four blogs to my blog list. Long over due to be added is AH's very insightful Trinitarian Life, one of my favorite reads. Also, a new find for me which looks very promising is John Paul Hoskins' blog Tolle lege, tolle lege. My friend, Doug Martin, has added yet another blog - Second Spring - to his portfolio. And, finally, another blog long overdue to be added: Reformed Catholicism. Be sure to check them all out.

Thursday, January 04, 2007

The Calling of Apostolic Churches in a Postmodern Age

I wrote the following reflection about a year ago for another context. Ben Meyer's discussion of the Virgin Birth (entry: December 23, 2006) over at Faith and Theology inspired me to dig it out of the archives for my readers. I'd appreciate any comments that you may wish to make.

+++++++

In my estimation, apostolic churches have a unique and peculiar calling within the kingdom of God to preserve and guard what can be termed the "Great Story" or "True Myth" (in Lewis' sense). This is the story of the New Testament: the mythos to which the early fathers provided normative articulation in ancient creedal and doxological symbols that are with us to the present day -- preserved in the liturgies of the great apostolic churches.

Yet, on this side of the postmodern curve, academic honesty compels the scholar to admit that "proving" the historicity of the mythos is impossible. But then it should be noted that disproving the historicity of the mythos is just as certainly impossible (a fact that the likes of John Shelby Spong and company disingenuously dismiss). Simply put, the mythos – the very object of the Church's faith – is not subject to historical or scientific investigation (either in proof or disproof). Rather it transcends critical inquiry, while, paradoxically, benefiting in the many new ways of understanding the Faith that may thus emerge from such investigation into the biblical milieu itself.

Be that as it may, the mythos or story is the starting point for all true Christian theology, whether one assumes the historicity of, say, the virgin birth or not. In this, as I said before, the apostolic churches have a unique calling. What would the Christian Faith be without the virgin birth? the resurrection? the ascension? or the parousia? What would it be without the doctrines of the Trinity? the Incarnation? or the Hypostatic Union? Make of these things what you will, but any supposed “Christianity” lacking the core elements of its mythos would be unrecognizable. To lose these things would be to displace the Christian Faith with something else, which at best would only be similar in appearance.

However, to answer more directly what must surely be the most pressing question raised by this line of thinking: The Christian Faith is not a belief in the historicity of the resurrection (as an end in itself), but rather faith in the resurrected Christ; it is not a belief in the historicity of the virgin birth (as an end in itself), but rather faith in the Christ who was born of a Virgin.

Monday, January 01, 2007

I'm back!

Actually, I didn't realize I would be "away" (from blogging that is). We just returned from spending the holiday with our families in Central Pennsylvania. I thought I'd have some time to blog while we were visiting. But as it turned out, we were much too busy.

My Roman friends might like to know that my oldest son and I attended a Christmas Eve Mass at a Roman Catholic parish -- St. Joan of Arc, Hershey, PA. The church was packed out! And it was only one of many services they were having that day. The service was a typical contemporary V-2 affair, and yes, I admit that I could not help musing that the Romans could learn a lot from the Episcopalians about how to "do" liturgy. But there is one thing the Romans seem to do right EVERY time I witness it, no matter what style of service (contemporary or traditional): the consecration of the elements. The solemnity of THAT moment was worth enduring all of the contemporary praise music beforehand. Even though I did not (and obviously could not) partake, I left that service fully nourished.

P.S. Blessed New Year to all my readers!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)