Saturday, April 07, 2012

The Quest Continues with "The Witness of the Empty Tomb"

Barth had never held or insinuated that the resurrection of Christ had been anything but a physical resurrection or that the Church's faith in the resurrection was rooted in anything less than historical event. Barth's earlier statements that seemed to dismiss the "empty tomb" were not about denying the existence of a grave or a sepulcher located somewhere in or around Jerusalem, but rather about the legendary character of the resurrection accounts found in the gospels.

Read the rest of the article here.

Friday, March 30, 2012

The Quest for the Mythistorical Jesus

...Jesus is not the kind of person that history typically remembers. Indeed, the shortcomings of "questing" for the historical Jesus is simply that what can be known about Jesus historically, apart from the rare incidental comment by otherwise disinterested observers (like Josephus and Suetonius), is relegated exclusively to the writings of his followers, particularly the gospels. The problem is, however, that the gospels are not "histories," at least not in the sense that we understand that term today; nor are they what we would call "biographies." Rather they are "faith-narratives," i.e., stories about the "Christ of faith."

Read entire article here.

Friday, July 27, 2007

Inspired by Barth: My Bullets on Election

· The decree of election is God’s eternal (i.e., ever-present) will to give himself in the incarnation of his Son, Jesus Christ.

· Christ is both the Subject and the Object of election. As Son of God, he is, along with the Father and the Spirit, the electing God. As Son of Man, he is also elected Man; albeit not merely as one elected man, but as the One in whom all others are elected.

· Christ is the all-inclusive election in which we see what election truly is – the unmerited acceptance of humankind by grace.

· The will of the Triune God in electing the Son of Man is the will of God to give himself to humankind in the incarnation of His Son.

· This self-giving is two-fold, both positive and negative (hence, a “double predestination,” if you will). Negatively, God elected himself in Christ to be our covenant-partner, and, as such, bore our merited rejection in his passion and death. Positively, God elected humanity in Christ to be his covenant-partner, and, as such, we are taken up into his glory in his resurrection and ascension.

· Reprobation and election are not two kinds of predestination based on two separate decrees. Rather reprobation and election are the two sides of the same eternal decree of predestination. Reprobation is Christ’s rejection for us that we in turn might not be rejected.

· The election of Jesus Christ includes the election of humankind. This does not mean primarily the election of individuals, but rather the election of the whole of humankind, which is manifested in history in the divine calling of the Church, the elect community, the Body of Christ.

· The Church, the community of the elect, stands in a mediate and mediating role as witness to the truth of God’s will for humankind in Christ. In this way, the elect community mirrors the one Mediator, Jesus Christ.

· The gospel is the declaration of the individual’s election in Jesus Christ, i.e., that Christ bore our merited rejection and gives to us his own glory.

· Individuals begin to live as elect by the event and decision of receiving the promise of Christ as mediated through the witness of, and by inclusion in, the elect community via baptism.

· Those who do not receive the promise of God in Christ live as those rejected in spite of their acceptance (i.e., their election in Christ).

· The relation of free will and grace in predestination is a mystery, yet those who continue to live in the reality of their union in Christ (i.e., those who persevere) are those chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Karl Barth's comment on the plurality of churches

Saturday, January 20, 2007

A Divided Church? by Hans Urs von Balthasar

by Hans Urs von Balthasar

from the Third Volume of the Theo-Dramatic

The division of the Church, brought about by sin, is rendered all the easier because of the distribution within her of various charisms and offices. At the very outset the community must be warned against envy and jealousy: someone else has been given something I do not possess; but, in the dispensation of love, it is for the greatest advantage of the whole in which I share. The eye sees on behalf of the whole body, and so on (1 Cor 12).

The administration of charisms presupposes selfless love on the part of all (1Cor 13). It takes only the slightest change of perspective to highlight the special nature of a charism--perhaps its striking and attractive side-making it seem more important than the Church's organic unity. Thus parties arise, often through no fault of the bearers of charisms. So Paul exhorts his hearers: "I appeal to you, brethren.... that there be no dissensions [schismata] among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment. For it has been reported to me ... that there is quarrelling among you, my brethren. What I mean is that each one of you says, 'I belong to Paul', or 'I belong to Apollos', or 'I belong to Cephas. . . .' Is Christ divided? Was Paul crucified for you?" (1 Cor 1: 10-13).

Of course, there is a difference between schisms within the Church and the ultimate schism that separates people from the unity of the institutional Church. But there can be no doubt that the former were the cause of the latter. Sin in the Church is the origin of the (equally sinful) separation from the Church. The process can last for hundreds of years within the Church--think of the long prelude to the schism with the East and to the Reformation--but it can always be traced back.

Not that this justifies the ultimate rupture. A slackening of the love that preserves and builds up the Church's catholicity is the beginning, however hidden, of all division in the Church: ‘ubi peccata, ibi multitudo.’ ‘Where there are sins. there is multiplicity, divisions, erroneous teachings and discord. But where there is virtue, there is oneness, union; thus all believers were 'of one heart and one soul'. (Origen, In Ez. hom. 9)

This raises the grave question whether, and when, the Church, divided internally and often externally as well, ceases to be a single person in the theo-drama. Two principles are crucial here. The first is that the Church, both as a community of saints and as an institution, is designed and equipped to sustain and save the sinners who dwell within her; she is *corpus permixtum* and must not separate herself from them as a Church of the "pure", elect", "predestined", and so forth.

To that extent, she has to continue to endure the inner tension between her ideal and her fallen reality, endeavoring to draw what is at her periphery toward the center. Thus the unity that encompasses her (the "net") is a principle of this kind: it can hold on to those who are estranged from her provided they have not deliberately renounced her.

At this borderline, however, the other principle takes over: theologically speaking, there absolutely cannot be a plurality of Churches of Christ; if such a plurality empirically exists, these several Christian churches cannot represent theological "persons". It follows that it is impossible, by a process of abstraction, to deduce some common denominator from the historical plurality and so posit an overall concept of the one Church; for the latter's unity is not that of a species: it is a concrete and individual, unique unity, corresponding to the unique Christ who founded her.

We would do well to listen to Karl Barth at this point:

‘The plurality of churches ... should not be interpreted as something willed by God, as a normal unfolding of the wealth of grace given to mankind in Jesus Christ [nor as] a necessary trait of the visible, empirical Church, in contrast to the invisible, ideal, essential Church. Such a distinction is entirely foreign to the New Testament because, in this regard also, the Church of Jesus Christ is one. She is invisible in terms of the grace of the Word of God and of the Holy Spirit, . . . but visible in signs in the multitude of those who profess their adherence to her; she is visible as a community and in her community ministry, visible in her service of the word and sacrament.... It is impossible to escape from the visible Church to the invisible.

'If ecumenical endeavor is pursued along the lines of such a distinction, however fine the words may sound, it is philosophy of history and philosophy of society. it is not theology. People who do this are producing their own ideas in order to get rid of the question of the Church's unity, instead of facing the question posed by Christ.... If we listen to Christ, . we do not exist above the differences that divide the Church: we exist in them.... In fact, we should not attempt to explain the plurality of churches at all. We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.... We should understand the plurality as a mark of our guilt’ (K. Barth, Die Kirche und die Kirchen. Theol., 9- 10).

We search the New Testament in vain, therefore, if we are looking for guidelines as to how separated churches should get on together; all we shall find there are instructions for avoiding such divisions.

While it is possible to say, with the Second Vatican Council, that "some, even very many, of the most significant elements and endowments that together go to build up and give life to the Church herself can exist" in those Christian communities that have deliberately distanced themselves from the institution of the Catholica; and while we may recognize that "men who believe in Christ and have been properly baptized are put in some, though imperfect, communion with the Catholic Church", this does not mean that such communities constitute separate theological persons over against the Catholica.

With regard to the relationship between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches, the question is whether mutual estrangement has proceeded so far that we are obliged to speak of two "Churches", or whether, in point of historical fact, unity "has never ceased to exist at a deep level" (L. Bouyer, The Church of God: "Theology of the Church").

There have also been attempts to suggest that there is a theological ‘necessity’ behind the phenomenon of schisms, ‘whether on the basis of the Old Testament schism between the North and South Kingdoms’ or arising out of the ‘primal split’ between Judaism and the Gentile world at the founding of the Church. With regard to the former split, however, the tribes of Israel had never been a unity comparable to that of the Body of Christ but a ‘confederation of diverse tribal groups’ that had only lately been united ‘in the person’ of the monarch. With regard to the latter split, it would be difficult to maintain that the Israel that refused Christ was responsible for disputes within the Christian Church; according to Paul, the unity of Christians is based on an entirely different principle (Eph 4:3 ff.) from that of the Jewish ‘sects’ (and Paul had been a member of one of them).

Precisely this principle of unity, however--the Eucharist of the pneumatic Lord--is a wholly new and incomparable principle, and this makes the initial split, which becomes aggravated into full-blown schism, to be practically irreversible. Urged by the most elementary sense of Christian duty, the ‘ecumenical movement’ must indeed tirelessly exert itself for the reunion of the separated ‘churches’. By doing this many partial successes can doubtless be achieved: for instance, the reduction of mutual misunderstandings, suspicions and denigrations.

But the fact remains that the group of churches separated from the Catholic Church has, by this very separation, necessarily gotten rid of the visible symbol of unity, the papacy, and this results in a situation in which our partners in dialogue (including the Orthodox) do not possess any authority which is recognized by all the believers and as such can officially represent these. In each case we are dealing with individual groups or bishops who regularly divide themselves into a party of agreement and a party of objection whenever reunion with the Catholic Church is contemplated. And, seemingly, the best that such groups can produce is an offer of abstract catholicity arrived at by overlooking real differences. We have already described such ‘catholicity’ as being plainly unacceptable.

However fruitful and instructive the ecumenical dialogue between Churches is, exemplary holiness will show not only that obedience to the Church (as understood by Catholics) can be integrated into Christian *agape* but that it is actually an indispensable part of the latter and of the discipleship of Christ.

Finally, while the Church's missionary task is to give witness to the world, the chimera of the divided Church shows just how shaky her self-transcendence into the world is. Indeed, it becomes increasingly precarious, the more Christian sects proliferate. Even if the worst stumbling blocks were overcome by making pacts between missions professing different beliefs, the fundamental stumbling block would remain as far as the recipient of missionary activity is concerned.

Nor can it be removed by portraying the diversity of Christian expressions as something harmless, something arising necessarily as a result of historical development, or even as something that brings blessing. To do this would simply be to obscure Jesus' original wish even more. To repeat the words of Karl Barth on the phenomenon of division in the Church: ‘We should treat it as we treat our sins and those of others.’"

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

The question of Catholicism

—Karl Barth,“Der römische Katholizismus als Frage an die Protestantische Kirche,” in Vorträge und kleinere Arbeiten 1925-1930, ed. Hermann Schmidt (Zurich: TVZ, 1994), p. 313.

Biretta tip to Ben Meyers over at Faith and Theology.

Friday, January 12, 2007

The Anglican Practice of Open Communion: A "Barthian" Take

.jpg)

DMARTIN ASKS: Do Anglicans believe that to share the Body and Blood of Christ is an act of full communion or not?

LEXORANDI2: Obviously, I can only give you one Anglican's perspective on this, but, YES, this is certainly the principle behind the practice of open communion in Anglican churches, even if institutionally (canonically) our respective ecclesial communities (i.e. churches) do not yet live into this reality.

I find it helpful to appeal to Barth's objectivist theology in support of the "open Table" practice, particularly the question of what is real and unreal about the Christian and the Church in light of our union in Christ. What is real about the Church in Christ (objectively and eternally so) is the Church's unicity and holiness. Disunity and corruption -- the very things we unhappily "live into" -- are unreal, and thus are things destined to nothingness. By "living into" them (through schism and apostasy) we improperly reify the very things that have been abolished in Christ.

That being said, over the course of my ministry I have become increasingly passionate in my advocacy for the "open Table." For, despite our tenacity to live into the unreal (with respect to such things as "orders" and tertiary differences in doctrine), I am convinced that the Anglican tradition attains her highest degree of "living into the reality of what we already are in Christ" in the celebration of the sacraments via her "open Table."

Obviously, she fails miserably in other ways...

(I direct my readers to revisit an earlier blog entry --Dialogue with Barth-- for a further elaboration on the real and unreal distinction.)

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Barth on a Budget

Friday, June 16, 2006

Barth and Synergism

In response to a question from a reader an earlier entry, I stated that "Barth's actualist soteriology has had such a profound impact on my own approach to theology that, as an Anglican and a Catholic, I find myself SET FREE to entertain and explore more synergistic models as relating to the existential moment of salvation."

Recently I've been reading another work by Hunsinger called Disruptive Grace (Eerdmans, 2000), which is a collection of studies that he wrote on Barth's Theology. In his article, "The Mediator of Communion: Karl Barth's Doctrine of the Holy Spirit" (1999), Hunsinger had this to say about Barth's understanding of human cooperation with divine grace:

Barth does not deny that human freedom "cooperates" with divine grace. He denies that this cooperation in any way effects salvation. Although grace makes human freedom possible as a mode of acting (modus agendi), that freedom is always a gift. It is always imparted to faith in the mode of receiving salvation (modus recipiendi), partaking of it (modus participandi), and bearing witness to it (modus testificandi), never in the mode of effecting it (modus efficiendi). As imparted by the Spirit's miraculous operation, human freedom is always the consequence of salvation, never its cause, and therefore in its correspondence to grace always eucharistic (modus gratandi et laudandi) [p. 165].

In an insightful footnote at the end of this last sentence Hunsinger observes that Barth's position brought about an "implicit resolution of the sixteenth-century 'synergist' controversy between the Philippist and Gnesio-Lutherans." Essentially Barth's position transcends the issue by taking something from each side of the dispute. With the Philippists, Barth acknowledges a true freedom in and the positive nature of the human response to the offer of divine grace, i.e. a "mode of acting" (modus agendi). With the Gnesio-Lutherans, Barth acknowledges the utter incapacity of human beings, in and of themselves, to respond to God's grace. The dispute hinged on whether faith was active or passive. The Philippists argued for a coincidence of the Word, the Spirit, and the human will in not refusing divine grace, which position the orthodox (i.e. Gnesio) Lutherans denied (and thus consequently excluded from the Formula of Concord). Barth's actualist soteriology allows for the Philippist idea of a coincidence of Word, Spirit, and human will by insisting that human freedom "is always a consequence of salvation, never its cause." For Barth, the human response is in nature "eucharistic" (i.e. thanksgiving and praise), not salvific -- thus addressing orthodox Lutheran concerns.

Alas, while I'm simply thrilled with Hunsinger's observation and application of Barth's theology to the Lutheran synergistic disputes, he leaves us begging the question: how might Barth's theology prove itself to transcend other Reformation/post-Reformation debates on these issues (e.g., Calvinist/Arminian; Protestant/Roman Catholic)? I intend to explore this matter more.

Until next time.

P.S. Incidentally, Pontifications recently posted an excerpt from E.L. Mascall's The Recovery of Unity (1958) that brings up this same Gnesio-Lutheran conundrum (namely, how can faith be conceived of as the one human act that is not a work?), attributing the problem to the underlying philosophical Nominalism of Luther's position. Personally, I think Mascall's argument is right on target. But I also happen to think Barth's "realism" addresses the conundrum rather well.

P.P.S. I found my copy of and I'm currently re-reading Hans Küng's Justification: The Doctrine of Karl Barth and a Catholic Reflection. I should have some insightful excerpts and/or some of my own reflections up on my blog over the weekend. 'Til then...

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

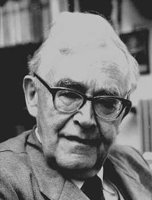

Hans Küng on Karl Barth

I found the following review of Hans Küng's Justification: The Doctrine of Karl Barth and a Catholic Reflection at this Link. Here's what Barth had to say about Küng's analysis and critique:

"The positive conclusion of your critique is this: What I say about justification—making allowances for certain precarious yet not insupportable turns of phrase—does objectively concur on all points with the correctly understood teaching of the Roman Catholic Church. You can imagine my considerable amazement at this bit of news; and I suppose that many Roman Catholic readers will at first be no less amazed—at least until they come to realize what a cloud of witnesses you have produced in support of your position. All I can say is this: If what you have presented in Part Two of this book is actually the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, then I must certainly admit that my view of justification agrees with the Roman Catholic view."

P.S. Note the figure standing in the background of Küng's portrait above. Interesting.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

A Modest Proposal: Barthian Implications on the Question of Justification's Formal Cause

Over at Pontifications I came across Al Kimel's recent discussion of the doctrine of Justification (We Can Earn it to Lose it). He begins with a quote from Matt Kennedy's recent posting at Stand Firm where Matt attempts to give a brief description of the differences between Anglican Evangelicals and Anglican Catholics on the question of justification.

I don't intend to critique either blogger in this entry. I merely point out these examples to illustrate that the main issue that continues to divide Western Christians -- Catholics and Protestants -- hasn't changed much in nearly five centuries with regard to the way the arguments on both sides have been presented; nor is this an issue that is going away anytime soon, despite genuine attempts on both sides to achieve rapprochement on what Luther described as the "articulus stantis vel candentis ecclesiae."

For theologians, this debate has not been so much about whether faith or works or some combination of the two justifies a person, as is popularly thought; but rather it has been about how theologians have answered the question "What is justification's formal cause?" For example, is the formal cause of the justification of the sinner the imputed alien-righteousness of Christ as most Protestants claim? Or are we justified by the gracious "supernaturalization of our natures" (to borrow Al Kimel's apt description of the Council of Trent's teaching on the matter)?

I'd like to make a modest proposal here, one suggested by Barth's actualist theology. I am particularly impressed by the strong distinction that Barth makes between the objective and existential moments of salvation. Despite many centuries of polemical hashing and rehashing on the subject, I suggest that Barth's insights might just serve to expose the inherently anthropocentric underpinnings and assumptions of the theological approaches of BOTH sides of this issue. If (as Barth's interpreter George Hunsinger describes it) the actuality and truth of our salvation does not depend on the existential occurrence of it, but rather the existential occurence of salvation is brought about by the actuality and truth of it, then it is simply wrongheaded to ground the event and occurrence of justification in something that happens to or within the individual sinner (whether as something imputed to, imparted to, or even "supernaturalized" within a person).

Rather a truly Christocentric approach to this issue would see the "formal cause" of justification (i.e., the actuality of salvation) as the ontological and vicarious identification of Christ with ALL humankind, which (as an existential encounter) becomes true for us even as we begin to recognize that it has always been true apart from us, and even against us. As St. Paul says, "...While we were yet sinners, Christ died for us" (Romans 5:8).

Until next time.

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Divine Grace and Human Freedom in Barth

'Divine grace and human freedom, as Barth understood them, can be conceptualized only by means of an unresolved antithesis. They cannot be systamatized or captured by a unified thought. Any attempt at resolving the antithesis will only result either in a false determinism (the risk run by Luther and Calvin) or in a false libertarianism (the risk run by Augustine and Aquinas). Barth's alternative to thinking in terms of a system here was to think in terms of the Chalcedonian pattern. Grace and freedom existed in the life of faith "without separation or division," "without confusion or change," and according to an "asymmetrical" ordering principle. "Without separation or division" meant that no human freedom occurred without grace, and no divine grace occurred at the expense of freedom. Grace granted the freedom for God that human beings were completely incapable of by nature, no only before but also continually after awakening to faith. Grace and freedom also existed "without confusion or change." Divine grace always remained completely unconditioned, even as human freedom always remained completely dependent on grace ... Finally, grace and freedom were related according to an asymmetrical ordering principle. Human freedom was a completely subordinate and dependent moment within the event of grace.'

--G. Hunsinger, "What Karl Barth Learned from Martin Luther" in Disruptive Grace: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth (Eerdmanns, 2000), p. 302.

Friday, June 09, 2006

Truth as Encounter: Part 3

This is the last installment from Hunsinger's work on Karl Barth that I intend to post before beginning the "Justification and Catholicity in the Third Millennium" thread, and it contains the most important seed for our discussion. Readers take note that (according to Hunsinger) Barth grounds justification/sanctification in the objective moment of salvation and sees vocation as the primary locus under which to explicate a theology of the Christian life and experience.

'The existential moment of salvation (as established through the event of encounter) is, it is important to see, understood primarily in terms of vocation rather than justification or sanctification. Justification and sactification are primarily conceived, in Barth's theology, as the objective aspects of salvation to which vocation is the corresponding existential aspect. Thus as Barth moves into part 3 of volume 4 of Church Dogmatics, where vocation is discussed, a much more recurrent and prominent use of "in us" can be found than in parts 1 and 2, where justification and sanctification as they occur "in Christ" are the respective topics of discussion. Much earlier it was suggested that objectivism is understood as the external basis of personalism, and personalism as the internal basis or telos of objectivism. To this it may now be added that justification and sanctification, as Barth presents them, can be interpreted as the external basis of vocation, and vocation as the internal basis or telos of justification and sanctification. As the internal basis of the objective moment of salvation, vocation is thus understood as follows. The event of vocation takes place through an encounter established and effected by God. In this event the integrity of both the divine and the human partners is so carried through that the encounter is self-involving for each. The goal of vocation is conceived as fellowship (IV/3, 520-54), and its essence is conceived as witness (IV/3, 575). As the existential moment of salvation, vocation is thus a matter of encounter, integrity, mutual self-involvement, fellowship, and witness.'

--George Hunsinger, How to Read Karl Barth, pp. 154-5.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

Truth as Encounter: Part 2

The next paragraph of the previous entry (with one more to follow). This one contains my favorite Barthian quote (alas not an actual quote of Barth):

Everything depends on noticing that Barth is attempting to think this matter through concretely rather than abstractly in his special (actualist) sense of terms. Everything depends, therefore, on seeing that he does not think in terms of the real and the ideal, but rather in terms of the real and the unreal (or of the possible and the impossible). What is real, possible, and concrete is what God has established in Jesus Christ. In Jesus Christ we see that God does not exist without humanity and that humanity does not exist without God. God without humanity and humanity without God are conceived as abstractions that do not really exist in the sense that they have no ultimate reality. God does not exist without humanity, because God has decided in Jesus Christ not to be God without us. Likewise, humanity does not exist without God, because Jesus Christ has decided in our place and for our sakes not to be human without God. Everything else about us, as noted more than once before, is regarded as an abstraction that is destined to disappear. By virtue of an existential encounter with God, our old situation (abstract, unreal, and impossible as it is) can and should be left behind even now. The salvation which as such was already true and actual for us in Christ thereby becomes true and actual in our own lives as well. What was already effective and significant de jure becomes effective and significant de facto (however provisionally) here and now.

--George Hunsinger, How to Read Karl Barth, pp. 153-4.

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

Truth as Encounter in Barth's thought: The problem of relating the existential and objective moments of salvation

As a prelude to a thread that I want to begin on "Justification and Catholicity in the Third Millennium," I have re-produced the following quote from George Hunsinger's How to Read Karl Barth. This should lay a good foundation for the discussion to follow.

As a prelude to a thread that I want to begin on "Justification and Catholicity in the Third Millennium," I have re-produced the following quote from George Hunsinger's How to Read Karl Barth. This should lay a good foundation for the discussion to follow.The problem of how to relate the existential to the objective moment of salvation is one to which Barth finds himself returning again and again. Especially because he lays such great stress on the unconditional priority of the objective moment, he realizes that the integrity of the corresponding existential moment is in danger of being underplayed or even undercut. "Reality which does not become truth for us," he writes, "obviously cannot affect us, however supreme may be its ontological dignity" (IV/2, 297). A salvation, an ontological connection of Christ to us, that remained merely objective with no existential counterpart would be a salvation that remained inaccessible and hollow. Yet a salvation whose truth and reality somehow depended on our preparation, reception, or enactment would be salvation in which the existential moment was at some point (whether overtly and covertly) grounded in us rather than in Jesus Christ. When the reality of salvation becomes true for us, Barth argues, then at the same time we recognize that it was already true apart from us (and even against us). Whatever preparation, reception, or enactment may have been involved (and continues to be involved), our recognition is not to be conceived as in any sense constituting the truth or actuality of salvation. Our recognition is simply our awakening to the fact that, in Jesus Christ, salvation's truth and actuality really pertain and apply to us as well, that we are included in them, that they are real for us, precisely by having been established apart from us. Our awakening does not do anything to make salvation as such true or actual. It merely means that we have come to see that we are not outside but inside this saving truth and actuality. But precisely because we are inside and not outside, it is necessary that salvation also take place in our own life. When salvation does take place in our life, however, it is not the existential occurence that brings about the actuality and truth of salvation, but rather the actuality and truth of salvation that bring about the existential occurence. The existential occurence is manifesting, not a constituting, of salvation's actuality and truth.

--George Hunsinger, How to Read Karl Barth, p. 153

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

More Thoughts on Barth: A Barthian Corrective to Augustinian Thought

Barth holds the Person of Christ as the central category of all theological reflection and inquiry. With respect to election, instead of an abstract impersonal decree we have the eternal will of God to give himself in the incarnation of his Son. Hence the hollow, contextless decretum absolutum of Augustinianism takes on personhood in Christ and a relational context in the will of the Persons of the Trinity.

This is helpful in orienting predestination, which otherwise views the incarnation as an after-thought of man-oriented divine decrees. Barth's christocentricity ensures that Jesus Christ is not merely the remedy of the Fall, but the “Lamb slain before the foundation of the world.” The divine decree of election is none other than Immanuel, "God with us." Furthermore, that Christ is both the subject and object of election wipes away the abstract notion latent in some Augustinian systems (e.g., Reformed thought) that divides the Godhead by picturing Christ as the victim of the divine will. As the subject of election he is the electing God. As the object of election, he is the elect Man in whom all others find their election. Barth's christocentrism also clarifies so-called “double predestination” by presenting Christ as both the Reprobate and the Glorified One.

For the Catholic thinker, Barth's understanding of election as mediated through the community of faith in its witness to Christ in the world also opens up a consideration of the Church and the Sacraments (even if Barth did not take us there himself). The Catholic understands Baptism as the sacrament of our incorporation into the Body of Christ, who in his Person is the constituting means of election. The Church declares the individual’s election, but not all will avail or prevail themselves of it as they reject or defect from the mediation of Christ.

Until next time.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Trevor Hart on Barth: Mapping the Moral Field

The man to whom the Word of God is directed and for whom the work of God was done -- it is all one whether we are thinking of the Christian who has grasped it in faith and related it to himself, or the man in the cosmos who has not yet done so -- this man, in virtue of this Word and work, does not exist by himself. He is not an independent subject to be considered independently ... whether he knows and believes it or not -- it is simply not true that he belongs to himself and is left to himself, that he is thrown back upon himself. He belongs to ... Jesus Christ ... He i.e., that which has been decided and is real for man in this Subject is true for him. Therefore the divine command as it is directed to him, as it applies to him, consists in his relationship to this Subject. (Church Dogmatics, 2/2, p. 539, quoted by Trevor Hart in Regarding Karl Barth, p. 80-1)

Trevor Hart comments:

...Believers and non-believers alike are situated (have their true being) within the dynamics of this one man's fulfillment of the covenant on their behalf. Consequently we are called to live in God's world as constituted thus, a world in which good human action is defined and realized on our behalf by Jesus Christ, in whose life, death and resurrection God has fulfilled the covenant and thereby established the kingdom in our midst, bringing our humanity (and with it creation itself) to its proper telos. Our action is thereby bounded and determined by our identification (not identity) with the one who stands before and among us as 'the elect of God'. It is characterized as obedience or disobedience accordingly as it confirms or contradicts our being as those who exist only in relation to him and his history. (Regarding Karl Barth, p. 81)

Monday, April 17, 2006

Summary of Barth's view on Election

The following is taken from old lecture notes of mine for a course I taught some years back at Cranmer House. This section is based on G.W. Bromily’s discussion in Chapter VII of his Introduction to the Theology of Karl Barth (pp. 84-98).

(1) Barth, like Calvin, understood the divine decree of election as eternal and immutable. However, he rejected outright the notion of election as an abstract decretum absolutum in the traditional Augustinian sense, considering such to be implicitly deistic. Rather the decree of election is God’s eternal (i.e., ever-present and active) will; and his eternal will is Jesus Christ. The will of God is known to us in the revelation of Jesus Christ, who is both the subject and the object of election.

(2) Jesus Christ is both the electing God and the elected Man. As Son of God He, along with the Father and the Holy Spirit, is the subject of election. As Son of Man He is also elected Man – the object of election. However, he is this not merely as one elected man but as the One in whom all others are also elected. His is the all-inclusive election in which we see what election always is: the unmerited acceptance of man by grace.

(3) The eternal will of God in the election of Jesus Christ is the will of God to give Himself in the incarnation of His Son. This self-giving has both a negative and a positive side – thus it is a “double predestination.” Negatively, God elected Himself to be man’s covenant-partner and as such he suffered death, bearing man’s merited rejection. Positively, the divine self-offering means that God elected man in Jesus Christ to be his covenant-partner and thus to be taken up into His glory as His witness and Image-bearer.

(4) Election should not be understood as one form of predestination, with reprobation as the other form. Such a view inevitably leads to some form of double predestination doctrine that works against the free grace of the Gospel. Rather, reprobation is viewed in terms of Christ’s rejection for us that we in turn might not be rejected. It is the negative side of predestination, which, like the positive side, has Christ as both its subject and object. In this may be seen that God’s predestination is his will in action, neither an abstraction from this will nor a static result of it (hence avioding the implicit deistic tendencies of the scholastic theologies).

(5) Divine election is primarily that of Jesus Christ but His election includes the election of man. This does not mean merely the election of individuals. Between Jesus Christ and individuals is the elected community, which in its mediate and mediating roles mirrors the one Mediator, Jesus Christ. It is only through this mediating election, by inclusion in the elect community, that individuals are elected in and with Christ’s election.

(6) The gospel declares that the individual is already elected in Jesus Christ, who bore his merited rejection. The individual begins to live as elected by the event and decision of receiving the promise. If he does not receive it, he lives as one rejected in spite of his election. If he does receive it, he now lives that which he is in Jesus Christ by the fact that in Jesus Christ his rejection, too, is rejected, and his election consummated. The task of the elected community is to declare the election of the individual.

Until next time

Dialogue with Barth continued...

....I would add that a subordinate soteriological existentialism, in all of its sub-categories, depends entirely upon an utterly gratuitous participation in -- or a "living into"-- the soteriological objectivism found in Christ. Without such an incorporation-- in which we may truly say that the church is salvation in the world, but only because she has been realized or translated into all that is objectively true concerning the last Adam -- we run the risk of making soteriological existentialism man-centered and autonomous. That is why I suggested that the notes of the church -- i.e. her unicity, sanctity, catholicity and apostolicity-- ought somehow to find their origin in Christ. Otherwise the Church would possess these virtues in herself.

I've known Mark for sometime now, and I can honestly say that he connects the dots faster than nearly anyone else I've ever known. The best thing is that he is humble and would never admit this and probably feels a little self-conscious about me extolling him in public.

Yet Mark has answered, or has at least begun to answer, the previous question he raised when the whole Barth thread began, namely (to paraphrase, if not to augment his question) -- "How can a sufficient catholic ecclesiology be built on Barth's observation that no particular church can make good on a claim of institutional ultimacy?"

Accepting Barth's objectivist theology compels us to conceive of the Nicene notes (i.e., unicity, sanctity, catholicity, apostolicity) as already actualized realities in Christ. The irony of Mark's earlier question is that the particular church that would make the claim of institutional ultimacy would essentially be claiming the actualization of these realities in itself, rather than in Christ. Meanwhile the church that made no such claim, and as such admitted to a more sobering view of the current divisions within Christendom (along with its own culpability in contributing to these sad divisions), would actually be "living into" the realities, especially that of unicity, better and more consistently than the first.

It's one of those "already, not yet" tensions, but not conceived of in the "unBarthian" sense that views present reality as a state of imperfection/corruption and future reality as a state of perfection/incorruption (i.e., unacheivable in this lifetime, but pursued by the Church nonetheless as an "impossible possibility"). Incidentally, conceiving of the "already, not yet" tension in this way lies behind the failure of the modern ecumenical movement to achieve any semblance of visible unity. Rather, unity, not disunity, is what is "real" about the Church IN CHRIST, because in Christ unity is ETERNALLY real. What is "unreal" about the Church is disunity, for division and schism are destined to nothingness, and eternally speaking already do not exist . In this life schism, division, and disunity are but mere "possible impossibilities": possible to the degree that, in this life we fail to "live into" the reality of what we already are in Christ as the Body of Christ.

Until next time.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

A Catholic Dialogue with Karl Barth: Beginning at the Center

One reader (a good friend of mine) recently asked, "How would a Catholic Anglican articulate a sufficiently Catholic ecclesiology, using Barth's definition?" (See readers comments in my posting "Food for Thought from Barth" http://www.blogger.com/comment.g?blogID=25190947&postID=114435868733104750) I've been pondering how I might be able to address this question all week. There is no easy answer without starting at the center and working outward through the implications of Barth's thought -- something that Barth did not live long enough to do completely himself.

The implications are where the rubber meets the road, where the hard work is done, and frankly where I find myself most exasperated with Barth as a dialogue partner. The Catholic reader of Barth discovers very quickly that for all of his erudition and clarity concerning the center of Christian theology Barth turns out to be just a man, and just as conditioned by his time and context as we are by our own. Simply put, Barth and I do not always agree, and certainly not about many things that I as a Catholic thinker hold dear. Nevertheless it is at the center of Barth's theology that one finds the pearl of great price, quite literally, for that center is Christ. And that is where we will begin.

There are two terms from Hunsinger's How to Read Karl Barth (cf. pp. 105-107) that I find quite helpful in my own dialogue with Barth. They are:

(1) "Soteriological objectivism," which refers to the idea that what took place in Jesus Christ avails for all without any exception, and is subject to no human condition or contingency whatsoever. Whatever takes place salvifically in us (e.g., faith etc.) is thoroughly and radically subordinated to what has already taken place for us in Christ.

(2) "Soteriological existentialism," which refers to the idea that though Christ and his work avails for all, no one actively participates in him and his righteousness apart from faith.

As Hunsinger explains: "The real efficacy of the saving work of Christ for all, the absolutely unconditioned and therefore gratuitous character of divine grace in him, the impossibility of actively participating in Christ and his righteousness apart from faith, the absolutely receptive and therefore nonconstitutive character of human faith with respect to salvation -- all these were axiomatic and nonnegotiable for Barth, because he took them to be the assured results of exegesis when the Bible was read christocentrically as a unified and differentiated whole" (p. 106-107).

In this quote we see soteriological objectivism and soteriological existentialism held in tension in Barth's thought. Christ's saving work is for all, not merely as a potentiality but as an ACTUALITY in Christ. There is no human condition that must be met in us to actualize our salvation that has not already taken place for us in Christ. The universality of Christ's work of atonement is upheld more so and more consistently in Barth than in any other thinker that I've come across; and yes, it would be fair to see this as a kind of "universalism." Yet it is a biblical universalism that we see in Barth as he adamently insists that the universal actuality of salvation in Christ be held in tension with the existential moment of salvation in the individual. To be faithful to the Bible is to acknowledge that Scripture clearly teaches that one's active participation in Christ is impossible without faith, and it is obvious that not all do or will come to faith.

When I first understood what Barth was saying, it was like understanding for the first time that the earth revolved around the sun not the sun around the earth. The theological applications of Barth's christocentrism are manifold, and we could hardly do justice to them in one blog entry. Nevertheless, let me just list a couple to get the juices flowing for future discussion:

(1) What implications might there be for the perennial Catholic/Protestant debates on Justification if our justification/sanctification are viewed as actualized realities in Christ?

(2) How does it change our understanding of predestination if election and reprobation are both understood as actualized in Christ?

(3) What do we make of sacramental efficacy in light of soteriological objectivism? Is there any place left for instrumentalism?

And finally...

(4) How might soteriological objectivism help us better understand the Church's unicity, holiness, catholicity, and apostolicity (i.e., the Nicene notes) in the context of division, heresy, and schism?

Until next time.

.jpg)