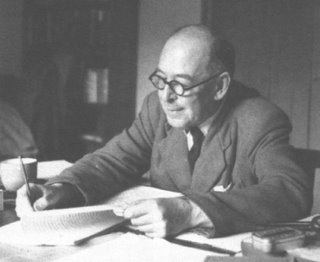

My thinking, indeed my whole theological method, has been driven lately by the idea of metaphor. As C.S. Lewis argued in his essay Bluspels and Flalansferes all language is incurably metaphorical, even that language intended by its speaker to be straightfoward and objective. It is just such an observation that led Lewis to believe that the more intentional we are in our use of metaphor the more meaningful our language is. Hence the poet speaks more meaningfully than the philosopher.

If I may borrow this observation, I would suggest that the liturgist speaks more meaningfully than the theologian. Both have their place in the church, but the discipline of theology involves the employment of reason to discern truth in the attempt to achieve objectivity. In doing this the successful theologian must attempt to minimize metaphor for the sake of simplicity in the hope of attaining clarity. On the other hand the Church through its liturgy, with its intentional use of metaphor, attempts to incarnate multiple levels of meaning that can never be completely comprehended or totally exhausted by reason. Simplicity is not the goal, nor is it ever the goal, of true incarnational worship. The Church through its anamnesis, or "effectual reenactment," of the story of redemption (the "true myth" of God using Lewis' meaning here) taps into a reality that cannot be detected by the senses or by empirical investigation -- all the more indicative of the importance of metaphor to en-flesh the truth of God. For this reason the Catholic priority of prayer over creed is essentially correct: the rule of prayer (lex orandi) is indeed the rule of belief (lex credendi).

Until next time.

11 comments:

DD,

Do you have an author, book or article that you would recommend on anamnesis, especially as you have defined it (effectual reenactment)?

Jason Kranzusch

I can't say that I picked up the term "effectual reenactment" from anywhere specific. It is a term that I have found helpful over the years to describe anamnesis. As for works, A.G. Mortimont's monumental _The Church at Prayer_ and Jones, et al. _The Study of Liturgy_ are great standard texts. I have benefited from Wainwright's _Doxology_ in the past, though I dare say I haven't cracked open the cover in recent times.

Dan

One caveat that I would suggest in the distinction you draw between metaphor and reason. Metaphors are ultimately about SOMETHING. Pursuing understanding of that something is the task of theology. It is, in St. Augustine's terms, faith seeking understanding.

As well, in conceiving the lex orandi to be the rule of faith we would do well to reflect on the observations of George Lindbeck, whose work "The Nature of Doctrine" I have found particularly helpful. He argues that doctrine, far from being simply propostitional truth or merely expressive of a prior spiritual experience is, rather, formative of experience itself. Doctrine is a kind of "grammar," he contends that sets "rules" by which we understand our spiritual impulses. As well, the doctrinal conversation in which we live, shapes our capacity to have experiences of a Christian sort. (Here he is, I think, simply arguing for a doctrine of the absolute essentiality of revelation. God must disclose his nature and show us our own true nature before we can begin to think rightly about God or understand our lives rightly.

So, the metaphor of liturgy and the reflections of the theologian are both critical. But the language of liturgy is primary as an enacted participation in the reality of the Incarnation and the witness of holy scripture.

That's a very helpful caveat, Steve. In my original draft before posting I actually wrote something like "That may be a bit of an over-generalization, but not much of one" concerning the distinction I made between the theologian and the liturgist. But in the end I took it out because it broke the flow of the text. And it was intended to be a "brief reflection." I really appreciate your insights. Always challenging and on target. Thanks.

Dan

This is a test. I've been experiencing some technical problems on this page.

Dan

Steve,

When you said:

"He argues that doctrine, far from being simply propostitional truth or merely expressive of a prior spiritual experience is, rather, formative of experience itself. Doctrine is a kind of "grammar," he contends that sets "rules" by which we understand our spiritual impulses. As well, the doctrinal conversation in which we live, shapes our capacity to have experiences of a Christian sort."

I'm wondering about the focus of this - in context, perhaps it is more clear, but my first reaction is that we don't live in "gramatical conversations" per se, and still less do we learn "grammer" before we begin to speak or understand a language. I would have said that we live in "liturgical conversation" from which doctrinal "grammer" can be abstracted, much as we abstract the rules of english grammer (years after the fact) from our english dialogue and patterns of speech.

Does this make sense?

Also, as you continue:

"Here he is, I think, simply arguing for a doctrine of the absolute essentiality of revelation. God must disclose his nature and show us our own true nature before we can begin to think rightly about God or understand our lives rightly."

I wouldn't argue with this at all, but simply extend the analogy, and say that the way God discloses his nature and shows us our own true nature is not by first teaching us the rules of a grammer, but by simply speaking to *us* - by establishing the liturgical conversation (the heart of which, of course, is the Word of Life himself, and those Words of Life which were proclaimed by him, and recorded so that they could be re-proclaimed from one generation to another) just as parents do with their own children even before those children can be expected to understand and respond to the "fullness" of the content of that speech, still less to correctly parse the grammer behind that speech.

Is this making sense? Am I mis-understanding what Lindbeck has written?

Pax Christi,

JJH

Jeff,

Lindbeck's point, so far as I can recall in retrospect, is not that we learn grammatical rules before we engage in the communal discourse of our lives. Rather, he is observing that languages are ways of talking and thinking that impose their own limits on our way of thinking. They are filled with conceptual categories that either expand or limit our imaginations.

Hence, as we learn to speak, according to the 'grammatical' rules of a language -- even if we do not know them as rules, we learn are actually learning to think in a certain way.

Doctrines operate in a similar way he contends when we are thinking about religious experience. For instance, it is entirely unlikely that a Buddhist would be able to have an 'experience' of God as personally present and active in one's life as the Triune Father, son, and HOly Spirit. Why not? Because in a Buddhist doctrinal conctruct the rules of speaking about the ultimate are not personal, nor Triune, but impersonal and ultimately monistic (we all are part of the one cosmic essence).

As regards the way we experience God, God does, indeed, speak to us, but not in the first instance through the liturgical conversation. That is a secondary development that arose out of the Apostolic reflection upon the Word Incarnate speaking and being seen in Christ. So, any liturgical conversation must be disciplined now by the scriptural account of that Apostolic reflection and proclamation.

So, our liturgical conversation is with God, but it must never be far from our minds that we are speaking ABOUT the God whose is self-revealing in Christ as testified in the Apostolic witness. This does not entail that God teaches us "grammatical" rules of speech, but it means that God -- through the disciplining limits of Apostolic doctrine -- teaches us how we are to speak to him in worship and about him in theological reflection.

This sounds, even as I write it, hopelessly abstract. so, please let's continue the conversation.

Doc,

Your post was evocative of this sermon by Rowan Cantuar, http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/sermons_speeches/060321.htm.

It's an outstanding read on the elusiveness of human language to decode the Word.

C

Thanks for the link, Carlos. Hope all is well with you. Any update on your wife? Drop me a line.

Dan

Steve,

Thanks for this response - this is a helpful explanation.

Pax Christi,

JJH

Dr D,

Aixa's recovery has been extraordinary. Save for a pain in the neck (literally), she is pretty much back to normal. Hopefully, with ongoing therapy that will go away soon. I am indeed thankful for your prayers.

C

PS: Sorry for sending this anonymous... figured that my blogshot once is more than enough!

Post a Comment