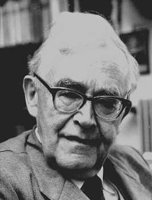

Recently I posted a quote from Paul Tillich that I want now to apply to the thread on the Invocation of the Saints. Earlier in the same article ("The Meaning of Symbols"), Tillich explained that a symbol participates in that to which it points. This is the main characteristic that distinguishes a symbol from a mere sign (The Essential Tillich, p. 42).

The proposal that I set forth for how we might better understand the practice of the Invocation of the Saints is a case in point. In that entry I stated that the Church employs the metaphoric language of direct address/petition to saints as an expression of her belief that our prayers on earth are joined in union with the prayers of the saints in heaven. Hence the Church's language of prayer in this case (I would actually argue in every case) is symbolic in Tillich's sense of opening up a "level of reality which is otherwise closed for us" (p. 42) -- namely, the Communion of the Saints.

Tillich's other observations are equally true when applied to the Invocation of the Saints. For instance, Tillich states that "symbols cannot be produced intentionally ... They grow out of the individual or collective unconscious and cannot function without being accepted by the unconscious dimension of our being" (p. 42). This observation accords very well with the historical development of the cult of the saints in early to late antiquity and its universal acceptance. The origin of the practice cannot be pinpointed to a specific locale or to a particular person or "inventor" as if it were some sort of innovation. Rather it is more accurate to suggest that the practice "emerged" (please excuse a term borrowed from another recent thread) in antiquity in a variety of locales, growing out of the "collective unconscious" of the Church Catholic in its formative period, and never significantly challenged until the 16th century Reformation (and only in the West).

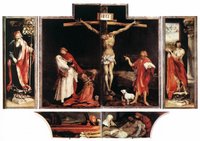

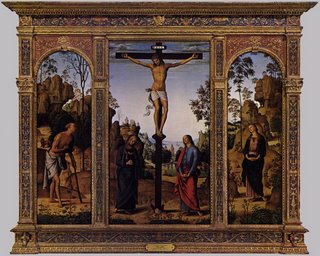

Finally, Tillich's observation that symbols "grow when the situation is ripe for them" and "die when the situation changes" is also consistent with what we see historically. The cult of saints grew out of the period of persecution and came into maturity in the period immediately following this -- during the era known as the "Peace of the Church" ushered in by Constantine. We should never underestimate the psychological momentum of this period, what Peter Brown aptly describes as "the working of an imaginative dialectic which led late-antique men to render their beliefs in the afterlife palpable and directly operative among the living by concentrating these on the privileged figure of a dead saint" (Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints, p. 71).

This observation also accounts for why the practice of the Invocation of the Saints, as well as the cult of the saints as a whole, fell into disuse and ended up "dying" under the changed situation of the Reformation. The churches of the Reformation, with few exceptions, allowed much of the rich symbolism (i.e., metaphor) of antiquity die, as such symbols were no longer associated with the "pure" doctrine of catholic Christianity as much as they were with the abuses of the medieval church. Catholic Christians of today might lament the throwing out of the proverbial baby with the bathwater, but it is quite understandable why the Reformation churches did what they did in their particular contexts.

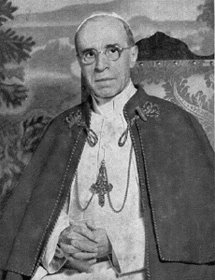

The strong suspicion of abuse over the practice of invoking saints persists among Protestant Christians to this day. Obviously, much of this is based on misconceptions of what the practice means to the typical Catholic and within Catholic faith and praxis as a whole. But I think the root of the general Protestant disdain for invoking saints goes much deeper than this. Over the years I have convinced many a diehard Protestant that there is nothing inherently idolatrous or particularly heretical in the practice. There have even been those who have been able to accept the practice on an intellectual level while continuing to be reticent and uncomfortable with it in praxis. Why is this? The answer, I believe, is that we are dealing with two different cultures -- Protestant and Catholic -- which find openings into Tillich's "levels of reality which are otherwise closed to us" by employing two different sets of symbols.

On the one hand it is not fair for the Catholic to expect the Protestant to incorporate what amounts to a foreign metaphor into a Protestant set of symbols. On the other hand, it behooves the Catholic of the third millennium to help re-connect the whole of Christendom, Protestantism included, to its roots in Christian antiquity. This begins with understanding and open minds on both sides of the issue.

Until next time.