In my short definition in an earlier post I described Anglicanism as the British expression of the catholic and apostolic faith as manifested in and mediated through the Church of England, et al. I realize that the two terms "catholic" and "apostolic" beg further clarification.

The second term is the easier of the two to define and to demonstrate historically. To be "apostolic" is to possess a demonstrable and continuous historical link of faith and practice from the time of the apostles onwards. Anglicanism recognizes herself as apostolic, while not denying it of others, claiming the ancient roots and uninterrupted history of Christianity in Great Britain from apostolic times as her own unique story.

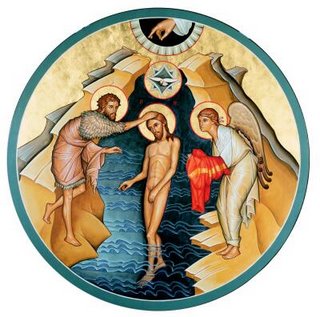

On the other hand, "catholic" is harder to nail down for Anglicans, particularly because of how the term has been employed in the post-East/West schism era (i.e., since 1054). Hence, Rome and Byzantium employ the term "catholic" more or less exclusively of their own respective communions, identifying both their pre- and post-schism development co-terminously with it. As a result, Rome and Byzantium since the schism have developed quite disparate understandings of what it means to be "catholic" that are mutually exclusive. We all know, at least in broad strokes, the end result of this sad millennium-old game of semantics between East and West: e.g., for the Roman, there is no "fullness of the catholic faith" without papal supremacy and infallibility; for the Orthodox, no catholicity without, say, full-blown Eastern iconology (just to name but one obvious example).

Anglicanism, on the other hand, did not come of age as a separate and independent tradition until the constitutional changes took place in the 16th century that made its "going-it-alone" posture inevitable. This is the most important factor that must be taken into account in understanding the Anglican definition of catholicity. Simply put, prior to her independent existence, the Church of England possessed at least two shared catholic identities: (1) pre-East/West schism -- a catholic identity in common with the undivided church; and (2) post-schism / pre-Reformation -- a catholic identity in common with the pre-Counter Reformation Roman Church.

For better or for worse, Anglicanism at the same time appropriated into its apostolic life and witness a strong Protestant character, which, on the positive side of things, meant a conscious return to the biblical witness in the reformation of its life and witness. (We could talk a lot about the negative side of this, but we won't here.) However, the Church of England did not go the sola Scriptura route of its continental counterparts in defining the terms and parameters of her perceived catholicity. Rather she consistently defined catholicity in terms of the Church of England's conscious continuity and identity with the understanding and practice of the undivided church (i.e., the first shared identity above) where such was consistent with the witness of Holy Scripture. This was the natural course for the newly liberated Church of England to go, for in leaving the moorings of Rome, she admitted to the deficiencies of the second shared identity.

This perception of catholicity was expounded by her first apologists -- Jewel, Hooker, and Field -- and has remained an indelible characteristic of Anglican identity ever since. Were the opinions or judgments of these men, or of the Church of England, or of her most eminent divines down through history, or of the worldwide Anglican Communion of subsequent generations, always "catholic" or even correct on every specific issue addressed? No, of course not. No Anglican would ever make this claim. The strength of Anglicanism is that, unlike the Roman and Eastern Orthodox bodies, it admits of no system of distinctively Anglican theology that is co-terminous with what it means to be "catholic." What is catholic within Anglicanism is what is shared with the undivided Church of the first millennium -- EVEN IF ONLY IMPLICIT. This means that catholicity within Anglicanism is something that is self-consciously lived into and realized in each generation of Anglican faith and practice, with each generation ideally contributing to a further and better explication of, and yes, even a discovery of, what it means to be catholic.

Of course, this task would be much easier if it were done in relation to all those who claim the name "catholic."